Addressing Social Drivers of Health: A Quality Improvement Approach to Developing Oncology-Specific Screening Tools

Advancements in cancer diagnostics and precision medicine have ushered in significant breakthroughs for patients diagnosed with cancer. However, the conditions in which

people live, work, and play—social determinants of health (SDOH), also referred to as social drivers of health—can be just as critical to an individual’s health outcome as factors like baseline health status, disease characteristics, and comorbidities. In the context of cancer, these social drivers can significantly influence a patient’s ability to receive a timely diagnosis, access specialized care, adhere to treatment plans, and obtain the necessary support needed to manage their condition.

Unmet social needs and health outcomes are widely recognized as interconnected, and this bidirectional relationship can hinder individuals from accessing the resources needed to address critical health care needs.1,2 Racial and ethnic minority groups, along with medically underserved populations, face significant and multifaceted barriers to receiving quality cancer care.1 As a result, these groups tend to experience higher rates of financial toxicity and poorer treatment outcomes. In fact, SDOH and their impact on people’s health, along with their contribution to health inequities, are a key focus of the Healthy People 2030 agenda initiated by the US Department of Health and Human Services.3,4 In addition, the digital divide—a gap between those who have access to technology, the internet, and digital literacy training and those who do not—has only widened inequalities in health care, research, and clinical trials.5

Given these barriers, there is an urgent need to implement systemic screening for SDOH that impact cancer care. To address this, the Association of Cancer Care Centers (ACCC)—in partnership with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and the Association of Oncology Social Work—developed a dedicated, oncology-specific SDOH screening tool and comprehensive resource library to better equip multidisciplinary cancer care teams across the US with the necessary skills to identify and address barriers to care.

What’s more, the impact of implementing such tools can be far-reaching, particularly in the realm of clinical trial participation. Clinical trial enrollment is significantly influenced by social drivers, often creating barriers that may prevent underserved populations from participating. By developing and implementing resources to improve the ability of cancer programs to better meet patients where they are, these tools can help facilitate greater access to clinical trials.

Quality Improvement Project: Shaping Tools to Identify Barriers to Care

Guided by expert insights from an advisory committee— comprising senior leaders in health equity, social work, and quality improvement from both academic and community-based oncology programs—ACCC facilitated a nationwide quality improvement initiative aimed at designing, testing, and assessing tools that identify and address patient barriers to care while also examining their influence on clinical trial participation.

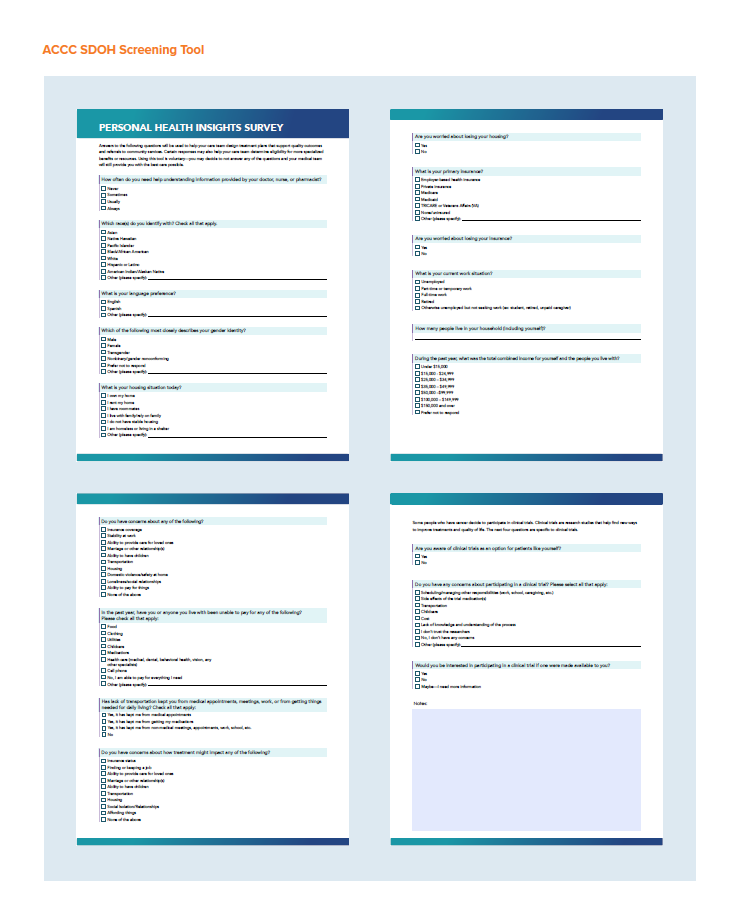

As part of this project, a comprehensive screening tool was formulated to assess patient barriers and concerns related to housing, finances, employment, insurance, transportation, and social and emotional support. The screening tool also includes specific questions to evaluate a patients’ awareness of and interest in clinical trials as part of their overall care and treatment options. In addition, ACCC curated a comprehensive resource library of nationally available publications, tools, videos, case studies, and other assets to aid multidisciplinary cancer care teams in identifying, assessing, and mitigating patient barriers related to SDOH.

Pilot Site Selection

Five cancer programs from across the US were selected to participate in a 6-month pilot study to implement and test the screening tool at their centers. As the goal was to evaluate the tool’s effectiveness in identifying SDOH and barriers to care across different populations, it was imperative that the pilot sites:

- Serve communities with limited resources

- Treat a high number of uninsured or Medicaid beneficiaries

- Serve a diverse patient population (eg, a high percentage of Black and/or Hispanic patients, located in varied geographic regions)

- Have the infrastructure to support future incorporation of the screening tool into its electronic health record (EHR) systems at a later stage.

The 5 cancer programs selected included AnMed Cancer Center in South Carolina, Christus Health in Texas, Mosaic Life Care in Missouri, Tennessee Oncology in Tennessee, and University Hospitals (UH) Seidman Cancer Center in Ohio. Individual quality improvement workshops were held with each pilot site to introduce the tools, outline the goals for implementation, and offer guidance on data recording and reporting. The project spanned several months, from May 2024 to January 2025, with interim reporting and cohort calls for team updates. To ensure consistent progress and successful implementation, pilot sites were responsible for:

- Designating a quality improvement project lead to ensure a high level of engagement

- Using the SDOH screening tool and ACCC SDOH Resource Library for a period of 4 to 6 months

- Screening a minimum of 25 patients from each site

- Completing an organizational pre-assessment, action plan, interim data reporting, and a final data report and evaluation.

An Inside Look at Experiences Using the Screening Tool

AnMed Cancer Center

AnMed Cancer Center, located in Anderson, South Carolina, serves approximately 1100 patients annually, with a patient population that is predominately White yet socioeconomically diverse. The center is located near a large lake and several major manufac- turing companies, which explains its mix of urban and rural patients. Most of the population speaks English or Spanish, with some patients signing via American Sign Language.AnMed Cancer Center screened 108 patients during the pilot, primarily at the beginning of a patient’s cancer treatment. New patients were screened shortly after diagnosis, with some patients rescreened upon recurrence or progression of their cancer. The tool was administered by nurse navigators who helped identify barriers to care for newly diagnosed patients with lung, head and neck, breast, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary cancer. AnMed staff reported that transportation and financial insecurity were the most frequently identified issues, and that the tool was effective in con-necting patients with internal resources (eg, financial coordinator, mental health counseling) as well as local and national assistance resources—such as the Cancer Association of Anderson, which helps patients with gas reimbursement, prescriptions, and nutrition supplements. While the tool was comprehensive, some patients found the screening process time-consuming. AnMed is currently considering simplifying its screening process and refining its approach to better meet the needs of its patient population.

Christus Health

Christus Health, a Catholic, not-for-profit health system based in Irving, Texas, serves a patient population of more than 2400 patients annually. With a catchment area that includes urban, suburban, and rural areas, its centers serve a wide range of racial and ethnic groups within its patient base. Most of the patients they serve speak English or Spanish.At Christus Health, the screening tool was primarily used in their surgical oncology clinic around the time of diagnosis for 28 patients, when they were first seen for consultation or before sur- gery. Social workers played an essential role in administering the screenings after referral from team members in the clinic or when patients reported needs/concerns on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® distress screening tool (Distress Thermometer). One of the primary challenges faced by Christus Health was addressing the emotional insecurities and anxiety that many patients faced because of their diagnosis. The tool helped identify critical barriers, such as the inability to afford medication or transportation to appointments, and facilitated the referral to both internal (eg, transportation grant gas cards, food pantries) and external resources on the local, state, and national level. Christus Health plans to continue using the screening tool and potentially expand it to other departments in the future.

Mosaic Life Care, Cancer Care

Mosaic Life Care, Cancer Care, located in St. Joseph, Missouri, operates over 60 clinical facilities across the greater St. Joseph area and serves a diverse population, with approximately 1100 oncology patients per year. The patient demographic includes White, His- panic, and Black communities, as well as increasing Sudanese and Chuukese populations. The area has predominantly low- to middle-income households, with many residents working in farming and other manual labor sectors. While English is the primary language spoken, Spanish, Sudanese, and Chuukese are also widely spoken, highlighting the need for multilingual resources to better support patients.Mosaic Life Care, Cancer Care, introduced the screening tool during chemotherapy education sessions, with the initial screening conducted by a nurse followed by a secondary screening with a social worker approximately 30 days later. A total of 24 patients were screened during the pilot, and the tool was used primarily to identify social and economic barriers that could impact patients’ ability to access treatment and to connect them with social workers and other support services. Insights from patients highlighted the usefulness of the tool in identifying issues such as transportation, housing, and financial insecurity, which often present barriers in accessing treatment. However, a significant challenge during imple- mentation was overcoming patient reluctance to discuss financial matters, particularly within the Spanish-speaking population. To better support its patients, referrals to internal resources, such as social workers and behavioral health consultants were often used along with integration of external resources (eg, transportation services) to help patients navigate barriers.

Tennessee Oncology

Tennessee Oncology, one of the largest community-based cancer care specialists in the US, is based in Nashville, Tennessee and serves approximately 12000 to 15000 patients per year across 18 locations statewide. Serving primarily rural areas, its centers provide care in a region marked by significant ethnic and socio-economic diversity. Common languages spoken include English, Spanish, Arabic, Farsi, Amharic, Tagalog, Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Nepali, Somali, and Russian, reflecting the multicultural nature of the region.Tennessee Oncology initiated the screening process early in patients’ care journeys, typically within their first few visits to the clinic. A total of 30 patients were screened during the pilot and the screening tool was implemented into the financial counseling work- flows at 2 clinics through the same financial navigator. Resources like food/nutrition assistance and copay assistance programs were used to help patients in these areas through local programs, including the local chapter of United Way and 211, a free, confidential service in Tennessee that connects people with local resources. A key focus at Tennessee Oncology was to evaluate how the screening tool could capture a broad range of social and economic needs while remaining feasible for use within its busy clinic environment. The team found that certain questions, such as those about clinical trials and financial barriers, were particularly useful but patients could benefit from more education to improve understanding. The clinic is now exploring ways to optimize their SDOH screening approach to maximize workflow efficiency and the patient experience.

University Hospitals (UH) Seidman Cancer Center

Located in Cleveland, Ohio, UH Seidman Cancer Center serves approximately 15000 patients annually through its primary medical center as well as 19 associated community-based cancer centers. The center caters to a combination of rural, suburban, and urban populations across 15 counties. While the primary language is English, Spanish is also commonly spoken. The communities it supports comprise a diverse mix of socio-economic backgrounds, with a focus on urban and suburban areas.At UH Seidman Cancer Center, the screening tool was used with 40 newly diagnosed patients, typically during their first or second ambulatory clinic appointment. The tool was administered by social workers at 3 ambulatory cancer clinics (urban and rural) during the pilot. The center faced challenges in meeting their initial goal of screening 50% of patients, partly due to workflow issues that hindered the integration of the tool into routine clinical prac- tice. Nonetheless, staff noted significant value in understanding the social and economic hurdles that patients faced, especially in terms of transportation and financial difficulties. Patients were connectedto transportation providers, financial assistance, social/emotional support, and other resources through local organizations like The Gathering Place, a local cancer support organization, and in 1 case, a social worker was able to source medical equipment for a patient to remain in their home for better support. The center plans to continue screening patients for SDOH and to leverage integration with their EHR system to streamline data capture.Outcomes and Insights from Pilot SitesImpact on Patient CareMost notably, the screening tool and resource library helped care teams across all pilot sites better capture patients’ unmet social needs and facilitated improved outcomes by connecting them with much-needed support, interventions, and community resources. Among the most frequently identified issues were financial insecurity, transportation challenges, and limited access to food; specifically, patient concerns directly identified through the SDOH screening tool included:

- Insurance coverage (lack of insurance or insurance instability)

- Ability to provide care for loved ones

- Financial insecurity (ability to pay for clothing, utilities, medications, food, health care)

- Housing (both current concerns and potential future instability)

- Stability at work; finding or keeping a job

- Transportation (issues preventing access to medical appointments)

- Language barriers

- Health literacy

- Loneliness/social relationships

- Marriage or other relationship(s)

- Domestic violence/safety at home.

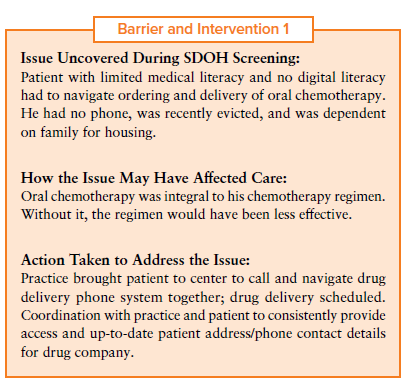

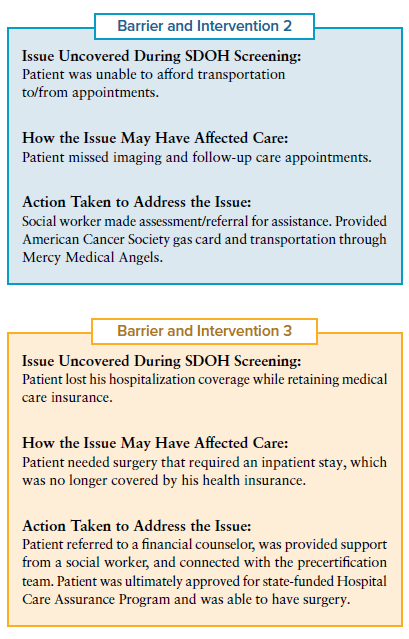

Pilot sites shared narratives and patient scenarios during cohort calls that illustrate the impact of the tools to address barriers. In terms of financial insecurity, sites noted that many patients report that they are able to manage all their costs; however, it remains unclear whether this is due to patients’ reluctance to disclose sensitive financial information, their having already been connected to resources, a lack of awareness, or other factors.

ACCC Advisory Committee member and chief executive officer of the Patient Advocate Foundation and National Patient Advocate Foundation, Alan Balch, PhD, shared this insight. “We found that patients don’t start to feel the financial strain until several months into their journey, [when] they start getting their first big bills. A lot of it depends on the type of insurance they have, as well as where they are in meeting their deductibles and out of pocket maximums.” Dana McDaniel, DNP, FNP-C, AOCNP, director of Oncology and Clinical Research at Mosaic Life Care, added that “What we’ve experienced is that the patients who are most reluctant to answer that question [financial/income related questions] are the ones that are afraid that they are going to have a negative impact from their medication reimbursement or that they may not be eligible for some kind of resource or copay assistance.” Greater support via social workers or financial navigation could help alleviate these concerns.

Access to Clinical Trials

The impact of SDOH screening tools extends beyond identifying unmet needs—they also play a critical role in addressing barriers to clinical trial participation. The representation of people from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds in clinical trials remains significantly low, and studies show that ethnic minority groups accounted for only 4% of participants in published randomized controlled trials in 2019.5

For many patients, awareness of clinical trials is often limited and misunderstood. At UH Seidman Cancer Center, 65% of patients were unaware of clinical trials, and 55% indicated they might have been interested if they had received more information. Similarly, at Tennessee Oncology, 60% of patients were not aware of clinical trial options, and 30% expressed interest in learning more. At Mosaic Life Care, some patients expressed concerns that the screening questions were aimed at enrolling them in clinical trials, while others were hesitant to participate due to fear of being “guinea pigs.”

AnMed Cancer Center found that the SDOH screening tool has helped raise awareness of clinical trial opportunities, acknowledging that many more patients than initially presumed were interested in participating. These insights underscore the importance of integrating educational efforts into the screening process to enhance patient engagement in clinical trials.

Feedback on the SDOH Screening Tool

Based on their experience over the 6-month period, most pilot sites found the ACCC SDOH screening tool to be comprehensive and easy to use. Three out of 5 sites rated the tool as “very comprehensive,” and 2 out of 5 considered it “somewhat comprehensive.” When evaluating the tool’s ease of use, 4 out of 5 sites rated it as “somewhat easy to use,” while 1 site considered it “very easy to use.”

Some patients found it difficult to engage with the screener, especially when the screening was conducted over the phone; pilot sites noted that the screening tool was better received in person. Other sites noted that the screening tool took more than 15 minutes to administer, which patients found burdensome. In fact, some patients asked to take the survey home to review it before completing it, suggesting that offering a take-home option might improve completion rates and accuracy. Mosaic Life Care and Tennessee Oncology reported that questions about income were frequently omitted by patients.

Several key reflections emerged regarding the screening tool:

- Language barriers: Non-English-speaking patients encountered challenges in understanding and completing the tool at some sites. Ensuring multilingual versions of the screening tool are available can help address this challenge.

- Income-related questions: Many patients were hesitant to answer financial questions, hindering the ability to fully capture financial insecurity.

- Health literacy: While the health literacy question adds value, implementing a consistent workflow to act on this information posed challenges at some sites.

- Digital literacy: Several sites noticed that the tool did not assess digital literacy, which is increasingly essential for patients to be able to access optimal health care in today’s high-tech environment.

While all sites intend to continue to screen for SDOH based on the value of information collected during the ACCC pilot, some plan to continue to use the ACCC SDOH screening tool, while others may use a modified version.

Feedback on the Resource Library

The ACCC SDOH Resource Library was also viewed as “some- what” to “very useful” by the pilot sites and sites considered the tool to be “very easy to use.” Sites reported that the resource library helped staff connect patients with relevant resources and some sites found it particularly helpful for identifying local, state, and national resources to support patients. All pilot sites indicated plans to continue to use the ACCC SDOH Resource Library alongside local resources.

Christus Health found great value in the resource library, stating that “The resource library gets to the heart of something that is so difficult with caring for cancerpatients—that resources vary widely based on where a person lives and what kindof cancer they have. Resources that are consistent and not changing often are needed to avoid spending an inordinate amount of time checking resources on a regular basis.”

Tennessee Oncology also expressed interest in sharing the resource library with local non-governmental and community-based partners, recognizing that the library’s resources could complement their established relationships and successful track that patients have seamless access to relevant resources and sup- port within the community. Reflections on potential improvements for the ACCC SDOH Resource Library included:

- Regular updates: While the library is valuable, it is essential to ensure that it is regularly updated with current, accurate, and accessible resources.

- Expanded housing resources: Providing both emergency and long-term housing options would be beneficial, offering proac- tive solutions for patients in need of stable housing.

- Stronger local integration: Enhancing the library’s ability to connect resources with specific community partners could fur- ther strengthen its impact, ensuring a more seamless coordination of care at the local level.

Looking Ahead: Sustaining Progress and Expanding Outreach

To ensure continued success and growth in addressing SDOH within oncology care, building upon these resources and identifying areas for further development is the next important step. Pilot sites have already outlined plans to expand the use of SDOH screening tools and the ACCC SDOH Resource Library, sharing these tools within their respective organizations. At Mosaic Life Care, the screening tool will be introduced to their inpatient oncology unit as well as their sister hospital oncology departments for potential wider implementation. Similarly, AnMed Cancer Center plans to share both tools and pilot findings with their nursing leadership, care coordination, and discharge planning teams. Beyond these steps, several key areas for further development have emerged through the quality improvement project, which could help pave the way for more effective implementation and use of the tools. One of the primary needs identified is staff education. Many staff members across pilot sites lacked familiarity with SDOH, highlighting the importance of providing more targeted education and training. Mosaic Life Care, for instance, suggested incorporating simulation and educational opportunities to help oncology teams build a stronger understanding of these issues.Another area for growth is improving the navigation of sensitive topics with patients. Nurse navigators have become increasingly skilled at addressing delicate SDOH-related conversations, even when patients are hesitant to discuss them. Greater integration and use of navigators can help improve a team’s ability to screen for, identify, and address unmet needs.

UH Seidman Cancer Center noted, “The project exposed that the real need is less about developing more screening tools and more about supports and standardizing more seamless and effective navigation into action and services.” record in coordinating care.

To ensure the sustainability of screening for SDOH and sharing the knowledge and insights gained from this pilot with broader networks, future steps include:

- Evaluating the integration of electronic SDOH screening tools

- Expanding the use of the tool to additional departments or affiliated facilities

- Streamlining workflows to ensure efficient integration of the tools into routine care processes

- Continuing to build staff capacity through training, especially on navigating sensitive SDOH topics

- Collaborating with local and national partners to identify and address gaps in available resources.

Through these steps and initiatives, significant strides are being made in improving patient access to essential services, deepening the understanding of SDOH in oncology care, and fostering an environment of continuous learning and adaptation that can enhance cancer care.

References

- Disparities in clinical research and cancer treatment. AmericanAssociation for Cancer Research Cancer Disparities Progress Report. May 8, 2024. Accessed February 19, 2025. cancerprogressreport.aacr.org/ disparities/cdpr24-contents/cdpr24-disparities-in-clinical-research-and- cancer-treatment/

- Heller CG, Rehm CD, Parsons AH, Chambers EC, Hollingsworth NH, Fiori KP. The association between social needs and chronic conditions in a large, urban primary care population. Prev Med. 2021;153(106752): 106752. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106752

- Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed February 14, 2025. odphp.health. gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Korn AR, Walsh-Bailey C, Correa-Mendez M, et al. Social determinants of health and US cancer screening interventions: a systematic review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(5):461-479. doi:10.3322/caac.21801

- Adedinsewo D, Eberly L, Sokumbi O, Rodriguez JA, Patten CA, Brewer LC. Health disparities, clinical trials, and the digital divide. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98(12):1875-1887. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.05.003

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACCC is grateful to the Advisory Committee, partner organizations, pilot sites, and others who graciously contributed their knowledge and time to this education program.

ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Chiara Acquati, PhD, LMSW, FAOSW

Associate Professor

Graduate College of Social Work, University of Houston

Houston, TX

Alan Balch, PhD

Chief Executive Officer

Patient Advocate Foundation

National Patient Advocate Foundation

Hampton, VA

Cheyenne Corbett

Senior Director, Cancer Support and Survivorship

Duke Cancer Institute

Durham, NC

Yuriko de la Cruz, MPH, CPHQ

Program Manager, Social Drivers of Health National Association of Community Health Centers Bethesda, MD

Debbie Dey, LCSW-C, OSW-C Oncology Social Worker Maryland Oncology Hematology Annapolis, MD

Heather Honoré Goltz, PhD, LCSW, Med, MPH

Professor of Social Work

Department of Criminal Justice and Social Work

College of Public Service, University of Houston-Downtown Houston, TX

Tracy Jenkins, MSW, LMSW

Financial Navigator and Oncology Social Worker Spencer Cancer Center of East Alabama Health Auburn, AL

Sunil Kripalani, MD, MSc, SFHiM, FACP Director, Center for Health Services Research Vanderbilt University Medical Center Nashville, TN

Scarlett Lin Gomez, MPH, PhD

Co-Lead, Cancer Control Program

UCSF Hellen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

San Francisco, CA

Lailea Noel, PhD, MSW, FACCC

Assistant Professor of Oncology & Health Social Work

Steve Hick’s School of Social Work, The University of Texas Dell Medical School

Austin, TX

Terry Portis, RN, BSN, MBA

Oncology Quality Improvement Coordinator

Northside Hospital Cancer Institute

Atlanta, GA

Teresa van Oort, MHA, MSSW, LCSW-S

Senior Project Manager, Quality Performance Improvement

UChicago Medicine

Chicago, IL

PILOT SITES

AnMed Cancer Center

Christus Health Mosaic Life Care Tennessee Oncology

University Hospitals (UH) Seidman Cancer Center

ACCC STAFF

Kimberly Demirhan, MBA, BSN, RN

Assistant Director, Provider Education

Rania Emara

Assistant Director, Editorial Content

Molly Kisiel, MSN, FNP-BC

Director, Clinical Content

Elana Plotkin, CMP-HC

Senior Director, Provider Education

Michael Simpson

Marketing Manager, Provider Education

Victoria Zwicker, MPH

Program Manager, Provider Education

In partnership with:

Made possible with support from:

Explore additional resources on SDOH at accc-cancer.org/SDOH.

The Association of Cancer Care Centers provides education and advocacy for the cancer care community. For more information, visit accc-cancer.org.

© 2025. Association of Cancer Care Centers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission.